Diving into water blaster statistics (2012): Part 3 – Weights .:

Diving into water blaster statistics (2012): Part 3 – Weights .:

This is a continued deeper look into some of the statistics I've measured over the years on various stock water blasters (Jump to: the first part or the second part). This particular article will look a little more at water blaster weights. As noted in other articles, all stats are pulled from the iSoaker.com database which is queried by using the iSoaker.com Product Listing.

What's in a Weight?

Unlike dimension statistics like length, width, and height, which are readily affected by the shape of a water blaster, weight reports, well, how heavy the sum of the blaster's parts are. Generally speaking, the type of plastic used from various model or brand of water blaster remains very similar, thus if a blaster is heavier, it tends to be larger or bulkier. Granted, the total amount of plastic used depends not just on the overall dimensions of a water blaster, but also the water blaster's wall thickness, layering, additional stylistic elements, and, of course, the complexity of the internals.

Furthermore, exactly what makes up a water blaster internals is not just plastic. Many water blasters use springs, tubing, metal trigger rods, metal screws to hold parts and casing together, and non-plastic pressure chambers (e.g. the rubber found in CPS/Hydro Power diaphragm systems). Thus, on top of the weight of the plastic casing, a water blaster ends up being heavier the more complex its internals tend to be.

Generally speaking, water blasters with more components on the inside tend to perform better. While not always true, manufacturers avoid putting a lot of materials where the consumer cannot see it unless it is needed for water blaster functionality. If a part from the internals could be removed without loss of functionality or structural integrity, chances are that part would be removed to lower manufacturing costs. There are, of course, examples of overly complicated water blasters that seem to make poor use of their internals (e.g. the Super Soaker Hydroblitz), but usually most blasters do make use of what they have (see: the iSoaker.com Water Blaster Internals section).

Dry Weight versus Filled Weight

Weights reported in the iSoaker.com database are for water blaster dry weights. Dry weight, as the name suggests, is the weight of a water blaster prior to being filled with water. Thus, it is the weight of all of the parts and casing or, in other words, how heavy a blaster is when empty.

Filled Weight is the term typically used for a blaster filled with water. Some argue that they wish to know what a water blaster's filled weight is since, in a water war, an empty blaster doesn't let one soak one's opponents.

The catch with filled weight is how it should be determined or defined. For small or pump-action water blasters, it is simpler to determine filled weight: one would simply fill the reservoir to the top, pump a few times to fill the internal tubing with water, top off the reservoir, then weigh. However, even in this simpler case, the question of whether the pump should be filled or not when weighing remains. Are users typically topping off their pump-action blasters?

Things get even more complicated for pressurized reservoir and separate pressure chamber blasters. For pressurized reservoir water blasters, some space must be left in the reservoir for air, otherwise the reservoir cannot be adequately pressurized to yield a good performing stream. Some would say that a reservoir should be filled no more than 2/3rds full; others may prefer 3/4th since that provides more water, though also means one will need to repressurize the reservoir more as it gets lower. For separate pressure chamber blasters that use air, for best performance, these pressure chambers (PCs) should be primed (pumped first with air) for better performance, but how much priming one does affects how much water can then be pumped into the PC.

As can be seen by the above, all these uncertainties and inconsistencies with how a water blaster's filled weight can be determined makes it very difficult to put a solid number behind it. However, since there is value in having a sense of how heavy a water blaster is when mostly filled, the idea of water blaster filled weight is going to be taken into consideration for the revised iSoaker.com Bulk/Encumberance rating stat which are being revised for next year. More on that to come in another article.

From Big to Small

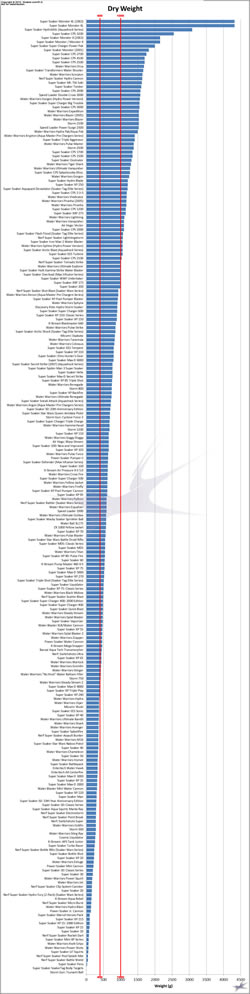

As shown in Part 1, the above chart shows the relative dry weights of the water blasters in the iSoaker.com database. Based on approximate feel, we will be grouping blasters based on their dry weight being less than 400g, between 400g to 1000g, and those weighing more than 400g. The demarcations follow our intuition that suggests blasters smaller than a Super Soaker XP240 should be relatively comparable, blasters larger than a Super Soaker CPS2100 should be relatively comparable, and those in-between make sense to compare, though water blaster lengths in these weight groupings tend to vary a little more.

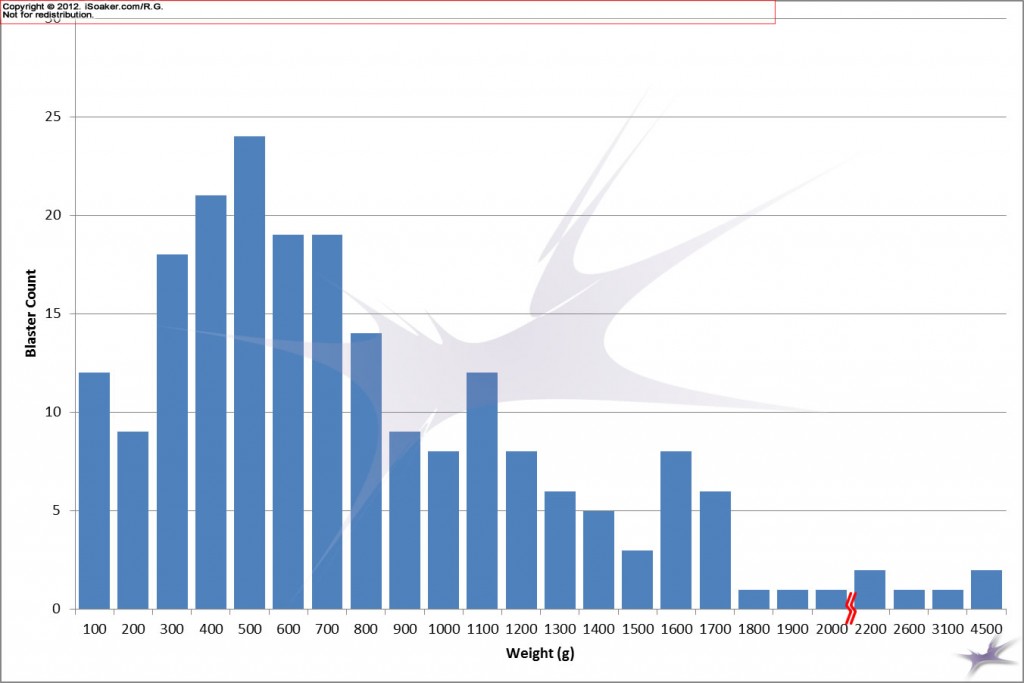

Another way to look at water blaster weights is shown below:

The above graph shows the number of blasters that fall into various weights grouped every 100g (as there are only a few blasters heavier than 2000g, those were given their own bar and intermediate bars where there are no blasters of a particular weight range are not shown). As the graph shows, most water blasters seem to fall around 400g to 500g (Super Soaker XP240 to Super Soaker Liquidator) with another peak ~1000g-1100g (Super Soaker 200 to Water Warriors Vanquisher) mark and a minor peak at ~1600g mark (Water Warriors Blazer to Super Soaker CPS2000). Sidenote: The Super Soaker CPS 2000 appears remarkably efficient and powerful for its overall dry weight!

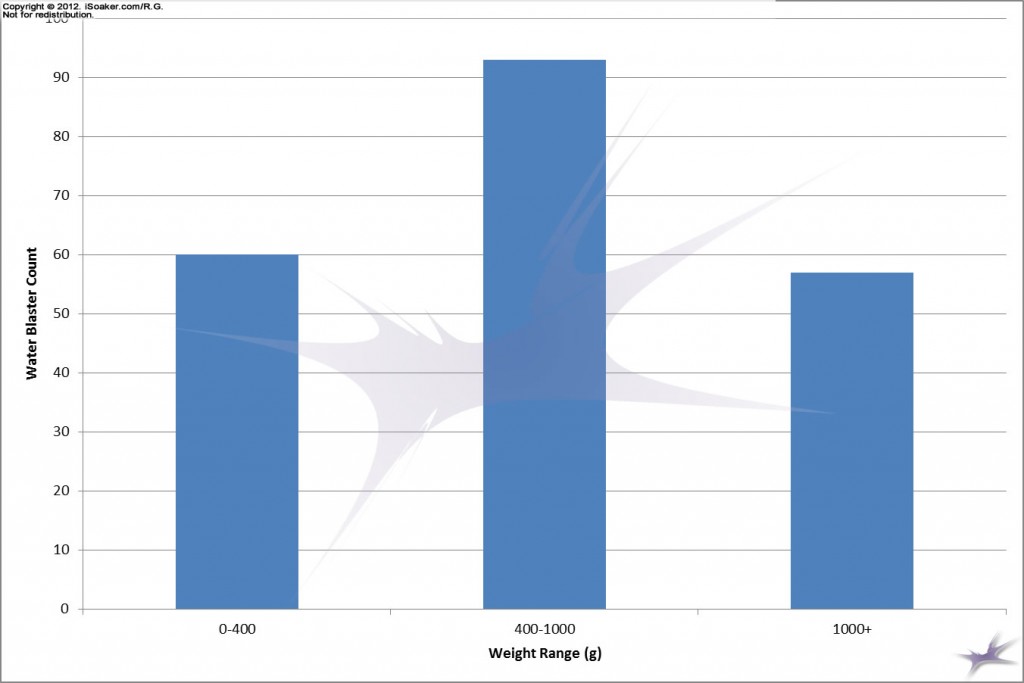

Grouping weights based on the <400g, 400g-1000g, and >1000g groups, we get the following.

These three groupings seem to nicely divide the various blasters apart with the two extremes having nearly the same blaster count and the mid-weight blaster class having the most.

In the end, looking at water blaster weights alone definitely does not tell the whole story about whether a water blaster is good or not. However, dry weight does seem to be a good basis from which reasonable comparisons between water blaster performance can then be gauged. Simply put, it is less reasonable for one to expect a blaster weighing less than 400g to perform as well as a blaster weighing more than 1000g since the heavier blaster tends to have more parts and mass to allow it to be more functional. At the same time, if a blaster weighs similarly to another, one would tend to expect that it should perform similarly. The water blasters that perform remarkably well for a given weight class are the water blasters we wish to identify and use.

Soak on!

Previous: Diving into water blaster statistics (2012): Part 2 – Lengths

Next: Diving into water blaster statistics (2012): Part 4 – Statistical Relationships